Lost Art

I’ve always found it odd, that very few web developers spend much time getting deep into HTTP and some of its goodies. Even though HTTP is a technology that is at the core of all web apps (and most mobile ones!), a lot of its benefits aren’t fully leveraged. Case in point, ask the next web developer you talk to to name five http request or response headers, and you’re likely to have yourself a short conversation.

I’ve always found it odd, that very few web developers spend much time getting deep into HTTP and some of its goodies. Even though HTTP is a technology that is at the core of all web apps (and most mobile ones!), a lot of its benefits aren’t fully leveraged. Case in point, ask the next web developer you talk to to name five http request or response headers, and you’re likely to have yourself a short conversation.

This is truly unfortunate, because there’s a LOT of great functionality to be had from this layer that’s built into almost every client that’s consuming your site and services (read no additional decencies, it’s already deployed).

The number of opportunities to get free features out of HTTP are even more numerous these days, especially with the popularization of RESTful services and more common service oriented architectures.

One of HTTP’s most often overlooked features is caching. I’ve blogged about client side caching before, but below is a tactical example of how it can be used.

You Should Probably Be Doing It Anyways

Here’s a nice blurb from the wikipedia Representational state transfer article:

As on the World Wide Web, clients can cache responses. Responses must therefore, implicitly or explicitly, define themselves as cacheable, or not, to prevent clients from reusing stale or inappropriate data in response to further requests. Well-managed caching partially or completely eliminates some client–server interactions, further improving scalability and performance.

Since restful services are supposed to describe the cacheability of their responses anyways, it’s not a terrible idea to implement http caching first, and then worry about server side caching.

Caching Example

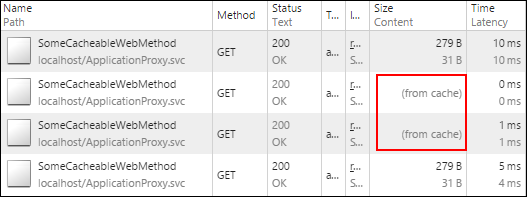

Below is a simple example of a WCF web service method that delivers a cacheable response where the client is instructed to cache the response for 10 seconds. Requests sent within 10 seconds of each other shouldn’t even leave the browser, they should be fulfilled from browser cache.

Let’s walk through it:

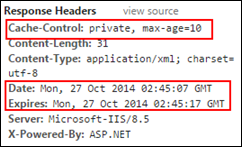

- 1. The Date property tells the client the time on the server. The client and server can be in two different time zones and a lot of properties like “max-age” are described in delta seconds. The delta is based off of the “Date” header, so you should supply it.

- 2. If there’s a chance that HTTP 1.0 clients may be using your service then consider including the “Expires” header, as 1.0 clients don’t know about Cache-Control (which is an HTTP 1.1 construct).

- 3. The Cache-Control header states that the method output is “private” which tells intermediary proxies to not this content. Browsers, on the other hand should cache this response, but to hang on to it for no more than 10 seconds.

public string SomeCacheableWebMethod()

{

var response = WebOperationContext.Current.OutgoingResponse;

response.Headers.Add("Date", DateTime.Now.ToUniversalTime().ToString("R"));

response.Headers.Add("Expires", DateTime.Now.AddSeconds(10).ToUniversalTime().ToString("R"));

response.Headers.Add("Cache-Control", "private, max-age=10");

return DateTime.Now.ToString("R");

}

When consumed on a browser, the headers and activity looks like the following:

If we wait for 10 seconds to expire the cache becomes stale and the browser issues a brand new request (fourth request in above).

Busting Through Caches

Well caching is great, but what if I don’t want a cached representation? Turns out HTTP has this construct built in too. Both the server and the client can tell intermediaries whether or not responses should be cached. A cursory web search will yield all of the details so I’ll omit them here with the exception of a client example.

When a client makes a request with the header “pragma: no-cache” or “cache-control: no-cache”, all of the caching intermediaries (from the browser, proxies, and the server) get out of the way and stop serving cached representations.

The first construct pragma is the HTTP 1.0 feature while, cache-control was introduced in HTTP 1.1.

Consider the same request same as before, but now with the cache-control: no-cache header added on (by the way, this is exactly what a browser does when you press CTRL+F5 [force refresh] in Windows browsers, check it out yourself).

Now the browser doesn’t even look in its cache, even though it has a cached representation that is within 10 seconds of the last request. The browser sends out a whole new request (with a caching directive telling intermediaries to not return cached representations).

When you issue a request with the header cache-control: no-cache, you’re going to bust through all of the caching constructs, regardless of the other caching directives that came with the original response.

The new set of requests looks like the below (notice that it doesn’t come from cache).

Hopefully the above at least piques some interest in client side caching. Using http proxies and thoughtful caching instructions can scale applications by orders of magnitude, and in a cost effective way.

What next?

Let Axian come to the rescue and help define your custom application strategy, develop a roadmap, work with your business community to identify the next project, and provide clarity and direction to a daunting task. For more details about Axian, Inc. and the Custom Application practice click here to view our portfolio or email us directly to setup a meeting.